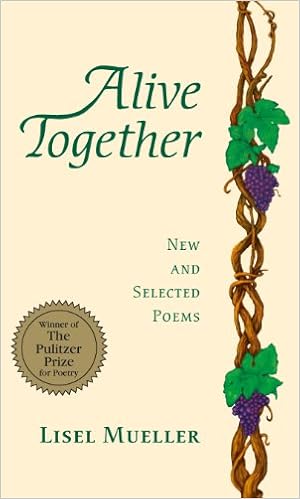

Today’s featured poem is from Lisel Mueller’s 1996 Pulitzer-winning collection, ‘Alive Together‘. The first section of this book includes poems about her personal history, memories of the past and thoughts on existence and mortality. Perfectly positioned as the first within that section, this is a classic Mueller poem – taking the ordinary and everyday and, with a well-honed precision of language and imagery, unfolding rich, intricate layers of meaning. Whether you find yourself reflecting on the latter or just enjoying her abilities to use simple language to evoke so much, you will be drawn irresistibly to read it again and again.

The choice of this particular poem and theme rather than something by a South African poet on apartheid (as I had originally planned due to Nelson Mandela’s death), might surprise some regular readers. So, allow me to digress just a bit to offer a justification of sorts. Perhaps, less of a justification and more of a description of how my train of thoughts led to this selection.

With the passing of a great soul, we find ourselves, sometimes, examining the shapes and textures of our own lives. Not that we would really want to trade our quietly-passing (in relative terms) days for the tumultuous unknowns that mark the ones of those passed. But, the opportunity to think of one’s life in the time of another’s death is something we all indulge in – consciously or not – like taking a much-needed deep breath of air into our lungs. And, whether we do this stock-taking by looking backward or forward, what we’re searching for cannot always be given voice, and, often, not even proper thought. But, perhaps, there is a fresh knowing in our bones of what matters in this world or a vitalized sense in our being of the current of life that still hums within and all around us. So, from “taking stock”, I was reminded of this particular poem, where Mueller, in this list format (long before listicles became popular, I might add), gives us a catalog of her own life’s events.

First, let me say what I really like about the 20 stanzas here. In describing the important milestones of her personal journey, she does not get maudlin. There is no self-recrimination, sense of inadequacy, bitterness. This is not to suggest that “maudlin” is an undesired quality in poems. Sometimes, we need the darker energies to help us get through our own dark tunnels. But, what this poem shows us is that, having got through those difficult times, it is possible to leave behind the darkness. Or, at least, it is possible to see through it finally as we were not able to at the time.

Also, there is never any excess in Mueller’s poems, the kind that Gombrowicz condemned in his diatribe ‘Against Poets’:

It is excess that tires in poetry: poetry excess, excess of poetic words, excess of metaphors, excess of nobility, excess of refinement and condensation which liken verses to a chemical.

Let’s now pause a bit on the title. This is not a “curriculum vitae” in the contemporary sense of an overview of a person’s qualifications and accomplishments. Rather, Mueller has used the Latin expression quite literally, for it means “(the) course of (my) life”. And, so, the poem gives us the course of her life and does not dwell at all on her poetic or literary accomplishments or qualifications.

And, one more thing before we get going here. The poem narrator is, of course, the poet. But, she addresses the poem to her husband, rather than the general reader out there like most poems tend to do. This is notable because the entire collection here is about her life with that husband and hence, the collection title of ‘Alive Together‘.

So, in stanzas 1 and 2, as Mueller starts with the place and year of her birth and sets the stage for the rest of her life story by alluding to the key events / forces that shaped it. Her biography tells us that she was born in 1924 in Hamburg, Germany, so we know that she is referencing the years just after World War I, during which a devastated Europe struggled to recover from the deaths of tens of millions of soldiers and civilians, not to mention the irreparable damage to economies. It was also a period of great political unrest and rumblings that led to World War II. These two simple stanzas remind us that our lives are shaped by a world that existed before we entered it. That bits and pieces of a larger past attach themselves irrevocably to us from the moment that we are born – entirely without our choosing or will.

Verses 3-6 then describe the early childhood world as a blissful existence in simple terms – love, acceptance, sensual pleasures. While she names specific family members, she does not refer to specific objects by their names and this is apt, as a child that young would not necessarily consider the latter as significant. So, for instance, school becomes, quite beautifully, a “building with bells”. Also, the people mentioned in these particular memories – parents, grandparents, teacher – are all adults. This tells us that, possibly, she was the oldest child in the family and, as such, had the luxury of basking in a lot of undivided adult care and attention.

And, finally, the insertion of the bookshelves in these early memories is precious, for they give us a clue to one of the poet’s long-lasting influences. In saying that they “connected heaven and earth”, we get the impression that, physically, they must have been imposing, floor-to-ceiling, perhaps. But, the other meaning, of course, is also that they are a source of ecstasy and joy, as books and stories are for many children.

Verses 7-8 present a more adult perspective. A knowing, an understanding of what is happening to Germany and, therefore, to her parents. The Jewish father, “busy eluding monsters” and the mother teaching her “the burden of secrets” tells us that, of course, all that wasn’t over with World War I. There is a lot more to come.

With adolescence, in verses 9-10, things start to get sharper. The highs and lows that comes with this particular time of one’s life are heightened by the political happenings in Germany, no doubt. From her biography, we know that Mueller, her parents and sister emigrated to America when she turned 15, so that must have been around 1939 – the year that World War II began. The grandparents stayed behind “in the darkness” and did not escape Nazi Germany, possibly due to the infirmities of old age.

Verse 11 does not tell us much about how she had to adjust and assimilate to a new world other than language being the thing to master. Her focus on language as the key to her assimilation gives us an inkling that, already, at that age, she must have been very attached to a life of words and literature / poetry. Other girls her age might have put the emphasis on something else – making new friends, fitting in, etc.

And, indeed, language continues to be the focus in verses 12-13, where it enables courtship and love with her future husband. It is also how she copes with the death of her mother, which “hurt the daughter into poetry”. This particular line, of course, is reminiscent of Auden’s lines for Yeats in ‘In Memory of W. B. Yeats’, where he said:

You were silly like us; your gift survived it all:

The parish of rich women, physical decay,

Yourself. Mad Ireland hurt you into poetry.

Now Ireland has her madness and her weather still,

For poetry makes nothing happen: it survives

In the valley of its making where executives

Would never want to tamper, flows on south

From ranches of isolation and the busy griefs,

Raw towns that we believe and die in; it survives,

A way of happening, a mouth.

This reference to Auden’s poem is intended to remind us of the way poetry survives everything, even grief. The lines after “Mad Ireland hurt you into poetry.” are, likely, what Mueller wants to call to the reader’s mind.

Verses 14 and 15 turn to her own family life – raising her daughters with her husband. And, how “the glorious, difficult, passionate present” pushes aside memories of the past or any dreams for the future, even though the threads keep all the knots connected together, so that there really is no escaping, just, if you will, a respite.

And, then, in 16 and 17, as her own children grow up, she tells us about her lonely father’s dying. After so many years of the mother gone, the father had lived on. But, eventually, his pain got the better of him.

The most interesting, I think, of all these verses, is verse 18. Mueller describes how, having lost both parents now and, in a way, having also lost her children (for they are no longer children), she tries to revisit or recapture her childhood, her past. But, she is unable to get back through that door. It’s there, of course, but, she cannot go back to it. There is much hidden in this verse that, probably, only those closest to Mueller will ever know. Did she mean that she visited the Germany of her childhood but found it was not there anymore? That does make sense, of course, because Germany, after the wars and The Berlin Wall, is a much-different country. Or, did she mean that she tried to go back to some unfinished business from her childhood that was interrupted because of having to grow up quickly and escape from World War II? Either way, this is, surely, something we have all done as grown-ups – tried to pick up some forgotten thread of our childhood and found that it did not lead us back to exactly where we wished it to.

Yet, for all these losses over the course of her life, the poem ends on a relatively positive note. In verses 19 and 20, Mueller describes how she has now passed into a different generation where she is older than everyone around her. And, even as the days and nights rush on by, her husband is by her side and they go together at their own pace, which is, “so far, so good”.

Curriculum Vitae

1992

1) I was born in a Free City, near the North Sea.

2) In the year of my birth, money was shredded into

confetti. A loaf of bread cost a million marks. Of

course I do not remember this.

3) Parents and grandparents hovered around me. The

world I lived in had a soft voice and no claws.

4) A cornucopia filled with treats took me into a building

with bells. A wide-bosomed teacher took me in.

5) At home the bookshelves connected heaven and earth.

6) On Sundays the city child waded through pinecones

and primrose marshes, a short train ride away.

7) My country was struck by history more deadly than

earthquakes or hurricanes.

8) My father was busy eluding the monsters. My mother

told me the walls had ears. I learned the burden of secrets.

9) I moved into the too bright days, the too dark nights

of adolescence.

10) Two parents, two daughters, we followed the sun

and the moon across the ocean. My grandparents stayed

behind in darkness.

11) In the new language everyone spoke too fast. Eventually

I caught up with them.

12) When I met you, the new language became the language

of love.

13) The death of the mother hurt the daughter into poetry.

The daughter became a mother of daughters.

14) Ordinary life: the plenty and thick of it. Knots tying

threads to everywhere. The past pushed away, the future left

unimagined for the sake of the glorious, difficult, passionate

present.

15) Years and years of this.

16) The children no longer children. An old man’s pain, an

old man’s loneliness.

17) And then my father too disappeared.

18) I tried to go home again. I stood at the door to my

childhood, but it was closed to the public.

19) One day, on a crowded elevator, everyone’s face was younger

than mine.

20) So far, so good. The brilliant days and nights are

breathless in their hurry. We follow, you and I.

— From Lisel Mueller’s Pulitzer-winning collection, ‘Alive Together‘